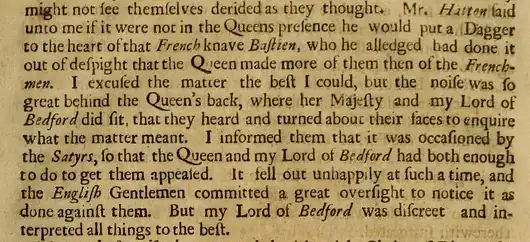

I was browsing through some very old English texts when I came across this page from The memoires of Sir James Melvil of Hal-hill, by George Scot (1683). The first thing that struck me was the anatomy of the capital letter Q in Queen. Its elongated tail dips well below the base line, and if you peer closely at the fourth Q you'll see it curl slightly upwards. It's not the first time I have seen a similar font but I was wondering if that particular letter style had a name.

I know that lowercase letters that extend beyond the baseline are called descenders, but I didn't find any information about uppercase letters with flamboyant diagonal tails and ‘legs’,

like the ‘K’ and ‘R’ in Kingdom, King, Retreat, Reader and Retriev'd.

like the ‘K’ and ‘R’ in Kingdom, King, Retreat, Reader and Retriev'd.

- My last question; in the text you'll notice that each of the following nouns and adjectives: Hatten, French Knave, Bastien, Frenchmen, Bedford, English Gentlemen and Satyrs are in italics and each word begins with a capital letter. Why is that? When did this trend end?

I read this question Capitalisation of nouns in English in the 17th and 18th centuries and although it talks about the craze for capitalizing “important nouns”, it doesn't mention anything about italicized nouns.