In words like think and lank, we actually seem to be saying "thing-k" and "lang-k." Can anyone thing-k of any words or rules for sound use where this doesn't happen?

-

I've answered the question but I figure I've misunderstood the title "Are there any words in English where there isn't a “ng” before a “k” sound?" as there are just so many (book, took, look, hook, kick, quick, etc. ad nauseum). Is there a way you could clarify the question so that it's clear you're not after words like 'kick'? Or are you after words like these? – boehj Jun 06 '11 at 02:25

-

I meant words that have an "nk" in them. There seems to always be a ng sound between the n and the k. – Elizabite Jun 06 '11 at 04:17

-

Nasal place assimilation is a feature of English phonology. This rule applies to all words at the phonological level, so there are no exceptions. – nohat Jun 06 '11 at 04:46

-

4There are words that contain "nk" that are not pronounced with a "ng" - for example "unknown". But that should probably be considered cheating (since the "k" is silent), hence this is a comment not an answer :) – psmears Jun 06 '11 at 08:11

-

2@psmears "unknown" does not have a “ ‘k’ sound”, as the question specified. – nohat Jun 06 '11 at 16:16

-

3@nohat: That would be why I said "the k is silent" and that this is "cheating" and thus not worthy of an answer :-) – psmears Jun 06 '11 at 16:24

-

3I suppose it could just be me, but there's no "ng" sound when I say "incorporated." I'll point out that I don't pronounce the first syllable like "ink." Not sure if that makes any difference... – kitukwfyer Jun 06 '11 at 22:45

-

@kitukwfyer It is not just you. For me, the underlying pronunciations of e.g. "income" and "ingress" contain /n/, not /ŋ/. That's not to say that they never come out with [ŋ], but [n] is my intention, and if I don't talk too sloppily, [n] is what I'll say. Nasal place assimilation sometimes happens, but not always. It seems that various factors influence how likely it is that the speaker will utter [ŋ] instead of [n], e.g. whether or not they perceive the "n" to end a morpheme, and whether or not the /n/ ends a stressed syllable. – Rosie F Jan 13 '19 at 09:27

5 Answers

There aren’t really any words with this property. It is a rule of English phonology that nasals assimilate in place before stops, so all nasals before /k/ and /g/ are velar nasals—that is, it is always the case that words which are written “-nc-” or “-nk-” will be pronounced with the “ng” sound, the velar nasal.

It is possible, in careful speech, to produce an alveolar nasal (the “n” sound) before /k/ or /g/, but in normal speech all nasals are assimilated. Because /k/ and /g/ are velar stops, any nasal sounds that precede it will always be produced as a velar nasal, regardless of underlying form (or spelling). Dictionaries vary in whether or not they mark the pronunciation with the symbol for the velar nasal (ŋ) or not because the assimilation is predictable. Merriam-Webster, for example, seems to mark nasal place assimilation when the following consonant is not the onset of a stressed syllable or across a morpheme boundary.

Regardless of the symbols used in dictionaries, everyone pronounces these nasals assimilated, as velars. You may not think you’re pronouncing a velar nasal in those words, but in almost all cases you actually are. Even if you are speaking really carefully and attempting an [n] it is almost certainly an [ŋ]. This has been established by studies with acoustic analysis and is an uncontroversial feature of English phonology. Some languages have a much higher load on this distinction so they have much more precise timing in articulation, but English doesn’t have the kind of precision in timing synchronization for nasalization/place articulation for the nasal sound NOT to be a /ŋ/. In order to make a true [nk] or [ng] you would have to have completely raised the velum and halted voicing to stop producing a nasal before even beginning to move the tongue tip away from the alveolar ridge to articulate the velar stop following. In normal speech the tongue tip leaving the alveolar ridge is much faster than the velum raising and voicing is continuous until just before the onset of the stop, so you’re going to end up with a velar nasal.

This assimilation happens even across morpheme and word boundaries. When there is an underlying /ŋ/ (as in thing) this often affects preceding vowel quality, so when there is an underlying /n/ (as in thin) you may think you’re producing an [n] because you are using a different vowel than if there were an underlying /ŋ/ but you are actually producing an [ŋ] if the following sound is a velar stop like /k/ or /g/. For example, in thin king vs. thinking, what you hear as the distinction is not actually the position of the tongue during production of the nasal, but other acoustic cues. The main distinctions are actually in vowel quality, stress, and timing, not in tongue placement. Unless there is a very unnatural complete pause in production, the ‘n’ in thin king is produced as [ŋ].

- 68,560

-

That's what I was assuming, but I was wondering if anyone could come up with an acception to the rule, or something in a related language, phonologically speaking, I suppose. Thanks! – Elizabite Jun 06 '11 at 05:57

-

I speak Australian English. Does this apply to me? Just curious. 'Doncaster' doesn't seem to have any 'ng-ness' to it at all. I'm not conversant with linguist terminology however. I'll add some Thai/Lao examples to my answer to see if those also fail the test. – boehj Jun 06 '11 at 06:28

-

-

3Surely the real picture is more complex than "assimilation always happens"? I find in my own speech there are words where the assimilation must happen (or the pronunciation is "wrong") - e.g. thinking, banking; words where it would not be wrong not to assimilate, but I always do (even when speaking carefully) - e.g. income; and words that only assimilate if I'm speaking really fast (e.g. pin-cushion, non-canonical, ungrateful). It would be interesting to know (though probably hard to find out) which words in the language are least often assimilated... – psmears Jun 06 '11 at 08:57

-

@psmears: As nohat says, the assimilation may not happen in careful speech, and as your examples show there is a cline with 'nk' in the same morpheme more likely to stay assimilated even in careful speech than 'n-k' across a morpheme boundary. – Colin Fine Jun 06 '11 at 11:17

-

2Pin-cushion seems to be a really nice counterexample. The way I speak English, it seems quite a chore to put an 'ng' sound in that word. I can hear it in my version of a Southern Drawl, but in Australian English it certainly doesn't come naturally. – boehj Jun 06 '11 at 11:19

-

3@Colin: Yes - my point is that (a) the answer as it stands seems to deny the existence of that cline, and (b) it would be interesting to know what lies at the cline's extremes (the morpheme-boundary thing is at best a partial explanation :) – psmears Jun 06 '11 at 11:59

-

@Colin @boehj, you may not think you're pronouncing a velar nasal in those words, but in almost all cases you actually are. Even if you are speaking really carefully and attempting an /n/ it is almost certainly an /ŋ/. This has been established by studies with acoustic analysis. – nohat Jun 06 '11 at 16:14

-

1@nohat: Can you provide a reference to those studies about @Colin's and @boehj's pronunciation? ;-p More seriously though - if speakers think they are pronouncing /n/ and /ŋ/ distinctly in these cases, and listeners can distinguish them (e.g. tell thinking from thin king etc), then what's the basis for saying they're not? I can accept the statement that most speakers produce /ŋ/ far more often than they realise, but you seem to be saying something stronger than that? – psmears Jun 06 '11 at 16:36

-

@psmears, when there is an underlying /ŋ/ this often affects preceding vowel quality, so when there is an underlying /n/ you may think you're producing an [n] because you are using a different vowel than if there were an underlying /ŋ/ but you are actually producing an [ŋ]. What you hear as the distinction is not actually the position of the tongue, but other acoustic cues. Articulatorily speaking, English doesn't have the kind of precision in timing synchronization for nasalization/place articulation for the nasal sound NOT to be a /ŋ/. – nohat Jun 06 '11 at 18:46

-

As for "thin king" vs "thinking", here again the main distinction is actually in vowel quality and timing, not in tongue placement. Unless there is a very unnatural complete pause in production, the 'n' in "thin king" is produced as [ŋ]. – nohat Jun 06 '11 at 18:47

-

I appreciate your comments. I wonder if this rule holds in other languages. It's probably too much to ask whether my Thai examples fail the test as I don't know the language of phonetics. The hardest parts of learning Thai for me were to a) learn how to say 'ng' at the start of words, and b) how to hear it in conversation. Now I have a much better ear for 'ng' than before I learnt Thai. Thai speakers would be incredulous if they were told they were actually saying 'ง', not 'น' in the examples below. We'd end up with 'might drive', 'nonsense', 'nonsense', 'might write', 'nonsense', 'nonsense'. – boehj Jun 06 '11 at 19:26

-

@boehj, I don't know from Thai but in my updated answer, I noted that other languages may have a higher load on the n/ŋ distinction before stops, in which case speakers of those languages have to be more precise in their articulatory coordination and timing when producing those sequences. – nohat Jun 07 '11 at 01:49

-

1@psmears, @Colin with regard to the cline of (perceived) pronunciation differences, I think this is more a case of whether and how much the onset of the nasal is alveolar. In pretty much all cases, the offglide of the nasal will be velar, and this is what I mean by there is always assimilation. Yes, it is true that careful pronunciation will result of alveolar onset in the nasal, which "feels like" pronunciation of [n]. – nohat Jun 07 '11 at 01:53

-

@nohat - OK, that makes sense. It'd still be nice to know what the actual case is with Thai, but I guess this is the english.SE. Thanks for your input. – boehj Jun 07 '11 at 03:14

-

@boehj it's a great question for the proposed Linguistics stack exchange. Commit to the proposal and ask your question about Thai when the site goes into beta. – nohat Jun 07 '11 at 05:43

-

@nohat: Nice idea. I know nothing about linguistics, but there's no time like the present to get started. – boehj Jun 07 '11 at 05:58

-

1@nohat: Thanks for the info, that's very interesting :) But it does seem to be moving the goalposts: the question asks about "-nk-" words not pronounced with an "-ng-" sound, not about words where the sequence /nk/ doesn't assimilate into /ŋk/. Whether the distinction between "ng" ("thinking") and non-"ng" ("thin king") is made by alternation between /ŋ/ and /n/, or by vowel quality, timing, or something else, surely there's a valid question as to whether there are words where the articulation is the non-"ng" version (or closer to it)? – psmears Jun 12 '11 at 20:02

-

1@nohat: Then it should be transcribed as [nŋ] or [nŋ͡n] or [nˠ], not [ŋ]. For probably most speakers, there remains a clear distinction between "thin king" and "thing king", even speakers that don't raise vowels before /ŋ/. – Mechanical snail Sep 21 '12 at 04:38

-

Anyway, this is a detail of articulation: articulation is modulated by adjacent sounds, since the tongue can't instantly change position. But that fact gives no basis to claim that assimilation is complete and /ng/ never occurs. – Mechanical snail Sep 21 '12 at 04:45

-

-

2@Mechanicalsnail Besides others that work like yours, like sinking, planking, other possible minimal pairs include funky & fun key; linkage & Lynn Cage; twinkie & twin key; incarnations & in carnations; incoming & in coming, pancake & pan cake; syncope & sin copy. What’s happening with all these is the same as with cancan, mankind, non-conforming: when you split into two words on morphemic boundaries, the stop at the start of the second “word” becomes aspirated (and usually stressed), which interferes with the assimilation or perception thereof. – tchrist Sep 21 '12 at 11:29

Sure, there are plenty of words like that:

- income

- inculcate

- encode

- encomium

And so on.

- 151,571

-

2When I say these words loud and fast (which I think elicits a more natural pronunciation), I'm still hearing a velarization before that nasal consonant. What do you think? – Elizabite Jun 06 '11 at 00:38

-

4Well, it's not impossible to nasalize them, and dictionaries do give the ng sounds as alternate pronunciations for some of them. It's just that, based on usage, the dominant pronunciation given for such words involves a non-nasalized n. – Robusto Jun 06 '11 at 00:40

-

I guess I'm having trouble not putting an ng in front of the k, but you're right, and pronunciations can vary. Income and Encode are for some reason the two that I particularly can't "un-ng." Do you hear it more or at all on those, out of curiosity? – Elizabite Jun 06 '11 at 00:46

-

2

-

@Robusto, all 'n' sounds are nasal(ized), by definition. You probably meant 'velar'. – nohat Jun 06 '11 at 04:45

-

4

-

3

-

@Marcin, nope all speakers of English assimilate nasals before stops. You may not think you're pronouncing it with a velar nasal, but you are. It may be bi-articulated, but it is definitely at least partially velar. – nohat Jun 06 '11 at 16:15

-

-

3@nohat: You have repeatedly made that assertion. And when you say "all speakers of English", it appears to include non-native speakers. Can you point us to a study that has actually studied "all" (or at least a representatively large sample of) speakers (at least both American and British)? (For what it's worth, when I say "thin king" as opposed to "thinking", there is no velar nasal and there is a complete pause in production. I know what the velar nasal is, because it's a separate consonant in my languages, and I can assure you it does not enter unless I slur the words.) – ShreevatsaR Jan 07 '12 at 13:20

-

@ShreevatsaR nope. I guarantee your nasals are assimilated. Provide recordings of your speech and I can prove it. – nohat Jan 08 '12 at 16:44

-

@Marcin: I'm from England, and I have an 'ng' sound in all of those words. – Billy Sep 21 '12 at 10:13

-

-

-

Whether these remain distinct varies by speaker. For example:

- Some speakers assimilate everywhere, even across word boundaries. Quite noticeably, they pronounce in case as "ing case" [ɪŋˈkejs], and similarly in fact as "im fact" [ɪɱˈfækt].

- For others, only homorganic nasals assimilate (e.g. /n/ to interdental in in that [ɪn̪ˈd̪æt], and sometimes /m/ to labiodental in emphasis [ˈɛɱ.fə.sɪs]), and other cases retain a clear alveolar articulation. Some may even keep it alveolar before interdentals.

For the second group, there is a clear distinction between /nk/ and /ŋk/ (resp. -/ɡ/) in some positions, both within and across words: inculcate, increase /ɪn/- vs. inkling /ɪŋ/; thin king /ˈθɪnˈkɪŋ/ vs. thinking /ˈθɪŋˌkɪŋ/; raisin clumps /n.k/ vs. raising clumps /ŋ.k/.

/nɡ/ /nk/ within a morpheme

However, almost all the examples of such words occur across morpheme boundaries, where the first morpheme ends in /n/ (e.g. income). So then a possible refinement of the question would be, does /nɡ/ or /nk/ ever occur within a morpheme?

Well, some speakers in the American Midwest (and perhaps elsewhere), however, pronounce penguin as /pɛn.ɡwɪn/ [n.ɡ]. Wiktionary lists this as a second pronunciation. This sounds jarring and seems like an affectation to me, but it exists, and it's distinct from the same speakers' pronunciation of e.g. Engels.

Another possible example: Wikipedia says of "Vancouver":

Vancouver, British Columbia: Residents of British Columbia, or often other parts of Canada, will generally pronounce the first syllable as /væŋ-/ or vang-, displaying the consonant assimilation typical in English when /k/ follows /n/ (such as in "ankle" or "ranking"). English-speaking Americans and some Canadians from other regions tend to pronounce it /væn-/ (van-), resisting assimilation to the following /k/ sound.

/nɡ/ or /nk/ within a syllable coda

Another refinement: do they ever occur within a syllable coda? I think not; it's phonotactically forbidden. (For that matter, -/ŋɡ/ is also phonotactically forbidden, so we only need look at *-/nk/.)

- 1,954

I deleted another answer I put here as it seems to me I misunderstood the question.

Viewing the question a different way (the correct way?) there are the non- type words:

- nonconformist;

- non-canonical;

- noncompliance;

- noncototient.

Then there are:

- concatenate (a.k.a.

catfor the *nix geeks around these parts); - concurrent;

- concordent;

- Concorde;

- concrete.

Also: Doncaster, ironclad, oncology, uncanny.

The question asks "What about in other languages?" as well. I wonder if these fail the test put forward by @nohat.

Thai and Lao make extensive use of the 'ng', 'n' and 'k' sounds. They're more or less the same but I'll deal with Thai here.

- ง makes an 'ng' sound when used at the start or middle/end of a word;

- ณ, น make an 'n' sound when used at the start or middle/end of a word;

- ญ, ร, ล, ฬ make an 'n' sound when used at the middle/end of a word.

- ก, ข, ฃ, ค, ฅ, ฆ all make a 'k' sound when used at the start or middle/end of a word.

Therefore there are words such as:

- คนขับรถ which means driver. It sounds like kon-kap-rot.

- คนไข้ which means an ill person. It sounds like kon-kai.

- คนขาย which means a shopkeeper. It sounds like kon-kaai.

- คนเขียน which means a writer. It sounds like kon-kian.

- คนคิด which means a thinker. It sounds like kon-kit.

- คนเข้าเมือง which means immigrant. It sounds like kon-kao-mueng.

Obviously, what I'm doing here is building up words the way the Thai language does, on a base of คน, i.e. 'person'.

There are many other examples where a 'k' sound doesn't follow a 'ng' sound including: ขอนแก่น which is the name of a city. It sounds like kon-kaen... or [kʰɔ̌ːn kɛ̀n] or [kʰɔ̌n kɛ̀n] (whatever that means).

And now from Thai to a world language: The language of chemistry.

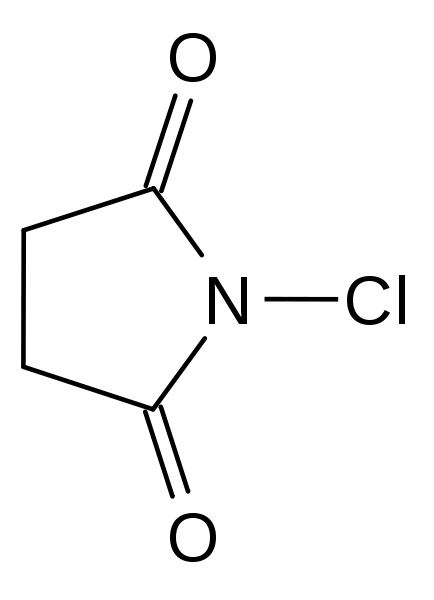

What about N-substituted molecules? I'll only give one example but there are an indefinite number of them.

Fig. 1 - N-chlorosuccinimide.

- 659

Examples with g and k (not mentioned in other answers): ungrateful, ingratitude, ongoing, ... ; non-kosher, unkind, ... .

- 1,278