As Prof. Yaffle mentions in the comments, if it were parallel to other forms, it would just be the letter l with an acute accent on top. I've never seen this form used for this purpose, but then again, l with an acute is not common, so it's possible that this form existed before Bullokar's book, and has only fallen out of use in modern times. L is the only letter out of l m n r with an ascender, so it makes some sense to use a different form of the accent with it: this occurs for the háček in many languages (some examples: Ľľ Ťť Ďď Ňň).

Then again, he seems to describe it differently from the other letters: on page 12, he describes it as having "a turne neere the top of it," while m and n are described as having "a strike over the middle." In any case, I will use ĺ to represent it in the rest of this post.

In terms of what sounds it was meant to represent, Bullokar describes this set of letters as "half vowels":

Lastly remain three: ĺ,ḿ,ń, called halfe vowells, because in their

sounde is included both a vowell and a consonant : but either of them

so short touched, that both yeelde but the time of a long vowell : to

these adde, ŕ, with his paier, as is before saide : this, ŕ, is of no

great necessity, but for conference with the olde : re : at the ende

of a sillable,and helpe in equiuocy. (page 22)

There are some examples later on. The letter "ĺ" seems to be able to represent multiple values:

- "baĺḿ" represents balm, "baĺd" represents bald, and "caĺ" represents call. Here it does seem to represent "dark l."

However, a normal "l" is used at the end of the syllable in other contexts, such as "bál" bale, "hél" heel, "elḿ" elm, and "bowl" bowl; all of these words also have dark l, at least in modern English. (I don't know if dark and light l had a different distribution in the past). Oddly, Bullokar distinguishes "baĺḿ: ointment" from "baulḿ: erb." He also distinguishes "caĺ" from "cau̧l, for the hed" and "cawl abou̧t the bo̧wellż."

- In other cases, it seems to represent a syllabic l, as in "litĺ" little.

Bullokar describes it as follows:

ĺ, ḿ, may make a triphthong with another vowell before them, as in:

caĺḿ: in Latine, Tranquillus, in French, Calme: eĺḿ-tré, in Latin,

Vlmus, in French Orme: hóĺḿ, in Latine, Ilex, in French, Yeuse:

but the voice doth rather yeeld, l: in, elḿ-tré, and in, holḿ, with

accent ouer: o. (page 25)

I'm not really sure what to make of it. It seems that Bullokar may have been in favor at this point of using distinct spellings to differentiate homophones ("equivocy") so even though he uses distinct spellings for

"caĺ," "cau̧l," and "cawl," I think they were supposed to represent the same sound.

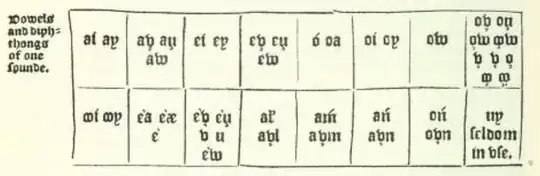

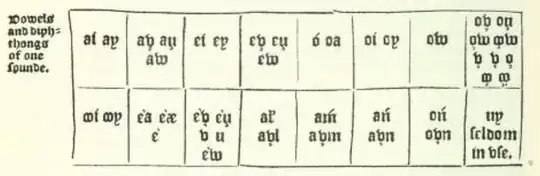

Bullokar seems to say that "aĺ" and "au̧l" represent the same sound in a table on page 23: