The simple answer is that you’re asking the question the wrong way about. In language, the central and most important way to inflect words is always what might be termed the ‘regular’ ones. The patterns that occur most frequently and are most flexible and applicable to the most roots. In English, the regular pluralising pattern is adding /z/ (with some assimilation and epenthesis rules). Everything else is irregular, including mouse/mice and louse/lice. So really, it makes more sense to ask why those aren’t mouses and louses in the plural.

If we look at it from a slightly more abstract angle and ask why these three words who are identical in the singular (except for the initial consonant) are different in the plural, we can answer it more usefully.

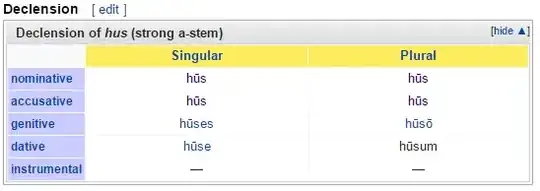

Let’s start with house(s). The reason why the plural of house is houses is that that ending is the regular pattern.1 That simple. In earlier stages of English, house had different plurals; but it was regularised to fit in with the most basic pattern of adding /z/. If we go back to Old English, the word was hūs (pronounced /huːs/, like ‘hooce’ in Modern English), and the plural was also hūs.

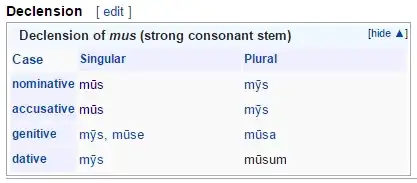

Mouse and louse were similarly mūs /muːs/ and lūs /luːs/ (like moose and loose) in Old English, but their plurals were mȳs /myːs/ and lȳs /lyːs/, respectively.

So why this difference?

Well, hūs is a neuter noun in Old English, while both mūs and lūs are feminine nouns. V0ight’s answer has already mentioned i-mutation (also known as i-affection), which is the historical cause of the different vowel in the plural of the latter two words. Historically, in Proto-Germanic, the plural ended in -iz (pronounced much like ‘-eez’ would be in English), and the high front vowel /i/ in that ending caused the preceding vowel to assimilate, to become more ‘ee-like’. And an /u/ that becomes more ‘ee-like’ almost always becomes /y/, as indeed it did in English. At some pre-English point in time, this final syllable was lost, but the change it had caused in the preceding vowel remained.

But this ‘ee-like’ plural ending was only used in the masculine and feminine genders; not in the neuter. In the neuter, there were various other ways of forming a plural, including not adding an ending at all. We can see from various comparative evidence that an earlier form of hūs also had an extra syllable lost by the time of Old English, but in hūs, the vowel in that extra syllable was an /a/, not an /i/ (Proto-Germanic *hūsa- was an a-stem, so its plural would have been *hūsō). Since there was no /i/, there was nothing to cause the i-mutation and change the /ū/ to /ȳ/.

So if we take it chronologically, starting from the Proto-Germanic stage, the development house and mouse went through went something like this (giving singular > plural pairs):

- hūsa- > hūsō // mūs > mūsiz (pre-English/Proto-Germanic: starting point)

- hūsa- > hūso // mūs > mȳsi(z) (pre-English: i-mutation, final syllables weakened)

- hūs > hūs // mūs > mȳs (~ Old English: loss of final syllables)

- hūs > hūs // mūs > mīs (late Old English: unrounding of /y/ to /i/)

- həus > həus(en/es) // məus > məis (Middle/Early Modern English: Great Vowel Shift diphthongisation of /uː/ and /iː/ to /əu/ and /əi/; house starts getting an explicit plural)

- haʊs ⟨house⟩ > haʊzəs ⟨houses⟩ // maʊs ⟨mouse⟩ > maɪs ⟨mice⟩ (Modern English: diphthongisation continued to /aʊ, aɪ/; alternative plurals of house disappear, leaving just one, regular plural)

If we focus on steps 3 and 4 here, you can see that hūs was the same in the singular and the plural, while mūs had a separate plural.

It is not uncommon for words that are under-marked (i.e., have different forms that are identical) to become marked (develop separate forms to make them less ambiguous), and that is indeed what happened to hūs here: people started applying the standard pattern of adding -es or -en (another formerly very common ending) to make it clearer that it’s a plural. That wasn’t (as) necessary for mūs, though, since the singular and plural forms were actually different there.

It does sometimes happen that a regular word becomes irregular if there is enough pressure (for example, dive has developed the past tense dove in American English because of the similarity to drove, strove, throve), but it is much, much more common that unpredictable, irregular forms are lost in favour of regular forms—so if anything were to happen in future to make the three words in this question the same, the expected development would be that mouse and louse become mouses and louses.

1 The ending is regular; the form as a whole is slightly irregular, since the stem-final consonant /s/ is most commonly (though not consistently) voiced before the plural ending. This is a pattern found with many words that end in unvoiced fricatives (/f θ s/); cf. mouth /maʊθ/ ~ mouths /maʊðz/, life /laɪf/ ~ lives /laivz/. For all three consonants, though, the plural voicing is sporadic and only happens sometimes—there is no rule.