The central issue of idioms is that the mechanics of their exact construction can be somewhat obscure. Unless there is documentary evidence, we are left with speculations. Which is why I believe the answers of RaceYouAnytime and Laurel are precious.

There should be no grammatical reason for using 'ever' instead of 'never' because (as you pointed out), the following sentence is grammatically correct:

It should never, never be allowed again.

Perhaps your hypothesis that double negative is playing a role; but that would for a purely practical reason (i.e. avoiding ambiguity): so that the people who are hearing such a sentence do not think for a split second that it could be a double negative, thus increasing the time it takes for them to dig the sentence; they would usually figure it out in the end, but precious time would have been lost. But in written form, I do not think that would be a problem.

A good clue could be in phonetics. Ever is an intensifier that sounds "right" (euphonic): in speech, it allows a cracking attack on the first syllab (-Ever), that one can amplify at will.

Indeed, we can imagine a preacher talking of the afterlife from the pulpit with a majestic:

And the smoke of their torment ascendeth up for -Ever and -Ever. (King James Bible, Revelation 14:11)

... which is a rendition of "in saecula saeculorum" of the Vulgate bible. And this should set us back to the early 17th century.

Litteraly it means "for the centuries of the centuries" (Greek εἰς αἰῶνας αἰώνων "to the ages of ages"), which is of course a metaphor of "eternity". I suppose, however, the translators of King James thought that translating it litterally into English would not have sounded idiomatic; and a mere "forever" would have been dull. Hence the powerfully sounding "forever ever" likely found its vogue thanks to the Bible and church sermons. In that case "ever" was the placeholder for the Latin "saeculorum".

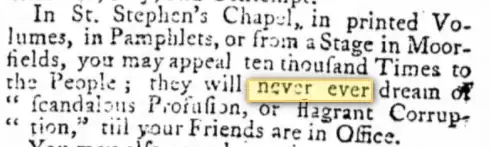

Turning the phrase into the negative (from "forever ever" to "never ever") must probably have been the next logical step in the 18th century. Furthermore, adding an "n" in front of "ever" would definitely have attenuated that attack. N is a nasal sound, so really amplifying ("never -Never") would have sounded like a neigh. That may have played a role in why English speakers (and therefore writers) stuck to "ever".

So the answer to your question likely traces back to a book written in Ancient Greek, long time ago!

As a bonus fact, the French translations of the Bible kept the Latin expression word for word:

Et la fumée de leur tourment montera aux siècles des siècles.

informal Very small; tiny. ‘itsy-bitsy candles that couldn't light the path of an ant’ ... Origin 1930s: from a child's form of little + bitsy (from bit + -sy). >>

– Edwin Ashworth Jun 16 '17 at 23:03