(1) We haven't spoken since the incident.

If the negation is regarded as being included in the situation described by the perfect, the perfect haven't spoken can be said to have a continuative/universal reading, because the perfect haven't spoken describes the situation of not speaking that continues from the incident up to now.

On the other hand, if the negation is regarded as being excluded from the situation described by the perfect and the negation is simply added to the perfect after the fact, so to speak, the perfect have spoken can be said to have an experiential/existential reading, because the perfect have spoken describes the situation of speaking that does not continue from the incident up to now. In this reading, you can say that We have not experienced the situation of speaking, or that such a situation has not existed.

Which is the correct interpretation of the perfect in (1)? In other words, should (1) be interpreted as receiving the continuative/universal reading or the experiential/existential reading?

And the same question for a non-verbal negation:

(2) You have done nothing but complain since we got here.

Which reading obtains in the perfect in (2)? The continuative/universal reading or the experiential/existential reading?

EDIT

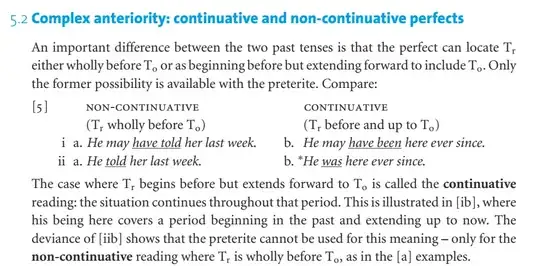

The Cambridge Grammar of the English Language (Page 141) discusses the difference between the continuative and non-continuative reading of the perfect:

Here, Tr is the time referred to (by the verb or verb group, e.g., have told, have been, told, was), and To is the time of orientation, which equates to the time of utterance in this question.