11 and 12 mean “one left” and “two left” respectively, referring to number 10. In other words, etymologically, they are NOT remnants of a base 12 number system. They are decimal, just like the -teen numerals.

So why do we have two distinct morphological implementations of the same way of counting?

Edit: I know that people used to count in 12’s a lot. But the unique pattern of “eleven” and “twelve” can’t be explained by that because etymologically, these names mean “[10]+1” and “[10]+2”. No connection to 12.

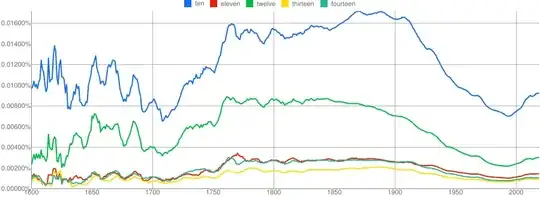

The fact that “twelve” is used more frequently than “thirteen” and “fourteen” could have resulted in more drastic sound changes, which could have given it its dissimilarity. But (1) that doesn’t explain 11, which has the same frequency as “thirteen” and “fourteen” yet doesn’t follow their pattern, (2) if that’s the result of a sound change only, it’s a pretty wild one. It would mean that -teen and that mixture of e’s and v’s in “eleven” and “twelve” both came from the same word that stood for 10. And this sound change would have affected other words, and it would have been described. But more importantly, “ten”, which is just as frequent as “twelve”, would have changed in the same way. But “ten” is way more similar to -teen than -lve.

I think it makes more sense to believe that these endings came from different words, and that there used to be more than one way of forming numerals, and that the -teen way eventually took over. But why didn’t it take over 11 and 12?