These two-letter words ending in -o are pronounced with the vowel /oʊ/: bo, go ho, jo, lo, no, so, and yo whereas do and to are pronounced with the vowel /uː/. Is there an explanation for the discrepancy in pronunciation?

-

I doubt anyone can provide any suitable answer to this. It's just one of the countless strange intricacies of the English language. – Urbycoz Jul 18 '12 at 10:36

-

We don't decide it. It just is. And sometimes it happens to change. – Colin Fine Jul 18 '12 at 12:26

-

I nearly never pronounce 'to' as 'too'. More often 'tuh'. – Kaz Dragon Jul 18 '12 at 12:39

-

3Exec summary: no decision is made. Pronunciation came first, then spelling was made up, they tried to make things consistent, but this wasn't particularly successful in English (no authoritative academy), and pronunciation has changed over the (hundreds of) years. – Mitch Jul 18 '12 at 12:59

-

2This has been closed as non-constructive, but I am reopening it to close it as a dupe instead. The simple answer is that the "o" in go was originally an /ɑː/, while the "o" in do and to was originally an /oː/. So they were always different to begin with, and even the Great Vowel Shift could do nothing about it, because different vowels shifted into different directions. Spoken language is primary; spelling is just a convention. So your question is kind of backwards. – RegDwigнt Jul 18 '12 at 14:26

-

I rewrote and reopened this question. It's definitely not a duplicate of the GVS question. It is a question about spelling which is just phrased in a misinformed way. – nohat Jul 18 '12 at 15:48

-

1Doesn't RegDwight's comment still answer the question though? – Andrew Leach Jul 18 '12 at 16:00

-

1Yes, I'm hoping he expands on it and makes it a proper answer. – nohat Jul 18 '12 at 16:10

7 Answers

The question posed

Why is “go” spelled with the same vowel as “do” and “to” since it is pronounced differently?

makes an incorrect presupposition. That's the cause of the problem.

Deny the presupposition and the problem goes away.

That presupposition is that

English spelling represents English pronunciation.

This is False.

The fact is that the spelling of modern English words does not give more than a vague guide to their pronunciation.

Vowels, especially, are terribly inconsistent, because there are fourteen phonemic vowels in American English (see the list here -- there are even more in other dialects), all represented by only five vowel letters, in many traditional ways, all inconsistent. Each way was designed centuries ago by people who knew no phonetics, spoke many languages and dialects (not all of them English), and thought they were writing Latin.

Any dictionary will tell you the spelling of English words. A good dictionary (which American dictionaries are not, alas) will also give the pronunciation in IPA or Kenyon-Knott. Spelling and pronunciation are separate, and should be learned separately, like the singular and plural forms of German nouns.

So the answer is that go is spelled with the same vowel as do and to because that's how they're spelled. There is no other reason. No matter what your English teacher told you. Sorry; it's not their fault, though -- they were taught this lie, too.

- 107,887

-

-

5The problem is that English spelling does represent English pronunciation, for most words, most of the time. It's more than just a vague guide. An educated person can guess the pronunciation of a word based on its spelling and be right the vast majority of the time. The exceptions to this all have explanation; spelling is not random. – nohat Jul 18 '12 at 17:09

-

2Indeed, that's true. Provided one wishes to learn Middle English, historical phonology, English history and dialectology, and Indo-European linguistics. Then you can see the fossils and identify the species; but to everybody else it's just a bunch of rocks, and it's much simpler just to learn the pronunciations separately. – John Lawler Jul 18 '12 at 17:16

-

Also, many current homonyms, like 'grate' and 'great' used to be pronounced more literally, but sound changes made them converge. Presumably (for some pairs) this can allow prediction. But of course, you can't do this for...what is it...heteronyms(?) where the spelling has diverged but not the pronunciation. – Mitch Jul 18 '12 at 17:19

-

1@JohnLawler I do want to learn all those things. We're supposed to be English language enthusiasts! – nohat Jul 18 '12 at 18:39

-

1@nohat: I'm delighted to hear it. There are some materials here, here, and here. – John Lawler Jul 18 '12 at 19:09

-

1

How do we decide pronunciation for english words?

Pronunciation of many (probably all) English words has varied over time and from place to place.

As you have noted, spelling is not a foolproof guide to current pronunciation in any specific place. This is particularly true as spelling currently varies from place to place (e.g. color and colour).

We decide how to pronounce a written word in any of the following ways.

- By hearing how people around us pronounce the word.

- By looking in a dictionary that provides a guide to pronunciation.

- By guessing based on how we most often pronounce other words with a similar spelling.

The result may be judged correct in some places at some times yet be judged incorrect elsewhere or elsewhen.

Why 'go' pronounce as 'go' and not 'goo' [as in 'do']?

The idea of standardised spelling is a relatively modern one. Shakespeare quite happily wrote his name using many different spellings. It was only with the advent of dictionaries that spelling gradually became frozen in whatever choice of letters the dictionary compilers selected. The early compilers do not appear to have been especially concerned about consistency between spelling and pronunciation. Noah Webster was a bit of an exception.

Words that today have similar spellings may have, in the past, had spellings that differed more widely and which reflected different pronunciations. Such words may have originated in different languages and have spellings adopted from those differing languages - which may have had different rules of pronunciation.

So the contradictions you identify might arise from an unfortunate convergence of spelling changes or from a difference in source language or even from an arbitrary change in pronunciation (e.g. in "the great vowel shift").

- 10,147

- 32

- 46

As Reg Dwight said in a comment, they have different historical pronunciations:

the "o" in go was originally an /ɑː/, while the "o" in do and to was originally an /oː/. So they were always different to begin with, and even the Great Vowel Shift could do nothing about it, because different vowels shifted into different directions.

Go and do happen to be spelled the same because in Middle English, the time period when much of the current English spelling system was formed, their vowels were fairly similar (/ɔː/ and /oː/ respectively), and there are not as many vowel letters in the alphabet as there are vowel sounds in English. But they have never been pronounced the same.

I'm not sure, but I think "to" and "do" are spelled that way because they are function words. According to Wiktionary, the Middle English ancestors of "do" and "go" were pronounced with /ɔː/ and /oː/, the vowels that became /oʊ̯/ as in "goat" and /uː/ as in "goose". So based on modern English spelling conventions, we could expect "go" to be spelled as is, and "do" to be spelled "doo". Why the shift? I suspect scribes truncated it based on the general notion that function words should be one or two letters long while content words should be three or more (this is also why "are" is spelled with a silent "e" even though it's pronounced like "start" and not like "square").

While it would be naive to believe English spelling represents English pronunciation, there are well enforced rules that govern their relationship, and ambiguities almost always have reasons behind them. I assume it was about these reasons that the OP wanted to learn when they asked the question.

- 111

There are many, many more vowel sounds in English than the five traditional Latin vowels. So it is inevitable that the same letter will represent different sounds in different words.

At best, English spelling reflects Middle English pronunciation, not Modern English pronunciation. That means it was locked in before the Great Vowel Shift.

These two simple observations go most of the way towards explaining your mystery.

- 134,759

Because the English language has co-opted words from many languages, and then corrupted/changed them over time we have a variety of pronunciation and spelling rules...which are not inflexible (compare the pronunciation of words by an Essex native with that of a Geordie, for example)

There are general guidelines which do broadly work - as long as you know or can guess the origin of a word. Did it come from a Latin root, or one of the Germanic languages, or Norse etc.?

- 6,672

The original pronunciation of the word go was "goo", so that it rhymed with "too".

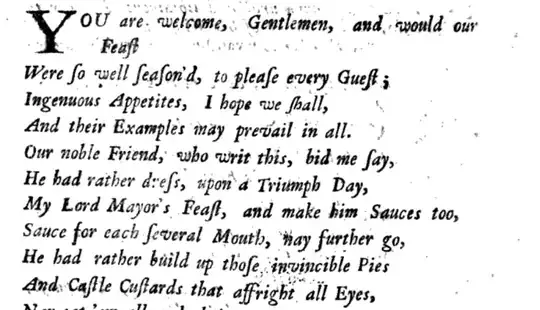

The following text is from the book "A wife for a month" printed in London in 1717:

Since I am not an expert in the history of the English language, I cannot tell you why the pronunciation has changed from "goo" to "go".

-

2

-

Yes, I am sure. In the preface of "The Royal dictionary Abridged" by Mr. Abel Boyer from 1751 it says that the diphthong OO sounds like the french diphthong OU. – Matan Cohen Oct 24 '19 at 21:37

-

On the other hand, that poem rhymes feast and guest, as well as shall and all. These words don't rhyme today, either. Why do you think too and go rhymed in the poem? – Peter Shor Oct 24 '19 at 21:50

-

The words "too" and "go" rhymed in the poem for the same reason "feast" and "guest" rhymed in the poem. Also, the words "shall" and "all" rhymed in the poem (the latter sounded like the former and not vice versa). There are many books that describe how English words were pronounced in the past. You can read them. – Matan Cohen Oct 24 '19 at 22:40

-

If there are so many books that describe how English words were pronounced in the past, why don't *you* read them and include some supporting evidence from them in your answer, rather than just citing a poem that has two other near-rhymes in it. – Peter Shor Oct 25 '19 at 15:01

-

I read the books. If you want to read them too, that's a good start. Type "English pronunciation" on books.google.com. Then you can set the dates to the years 1670-1800. And you will get all the evidences you need. Good luck! – Matan Cohen Oct 25 '19 at 18:56

-

-

Well, that's what I did. I justified my answer. you asked for evidences and I pointed you to the evidences. Is there anything else I can do? – Matan Cohen Oct 26 '19 at 00:10