I recommend Vellenman's book how to prove it, I think it will clear up many doubts.

#1 Apply truth value to the conditional premise as a whole, as follows.

P1. If I drop a ball ('p'), then it will hit the ground ('q')

P2. I dropped a ball ('p')

C. Therefore it hit the ground ('q')

You must first understand the difference between validity and soundness.

Validity (From Wikipedia):

In logic, more precisely in deductive reasoning, an argument is valid if and only if it takes a form that makes it impossible for the premises to be true and the conclusion nevertheless to be false.

This means that in a valid reasoning as long as the premises are true, the conclusion must ALWAYS be true.

Soundness (From Wikipedia):

In logic, more precisely in deductive reasoning, an argument is sound if it is both valid in form and its premises are true.

If the premises are not true, then it is not sound reasoning. So is your argument sound? No, since you could drop a ball and it won't necessarily fall to the ground. But it is a valid reasoning. That is, the proposition P1 is false, therefore the premises will never be true and therefore the conclusion could be true or false.

#2 Apply truth values to both p and q variables individually, as follows.

P1. If I drop a ball ('p'), then it will hit the ground ('q')

P2. I dropped the ball

P3. It did *NOT* hit the ground

Here you did not conclude anything but you could conclude what you want and the reasoning would always be valid, since if we apply modus tollens to P1 and P3 we get ~P2, then we have P2 and ~P2 a contradiction. In an implication where the premise will always be false then we can conclude anything, this is called vacuous truth as you said, there are many examples like this in set theory with the empty set.

For example, the fact that the empty set is included in all sets, but also that the intersection of two sets (without elements in common) is the empty set, or that the intersection between the universe (or any set) and the empty set is the empty set, or that the complement of the universe is the empty set. All these things can seem confusing if you don't know the vacuous truth.

But if you want to say that P3 is the conclusion, then the whole argument is a contingency or a fallacy, it is the same argumentative value as the fallacy of the converse. That means that the reasoning is NOT valid, since it is NOT a tautology (you can see it making a truth table).

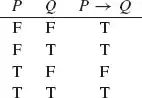

The truth table for "p => q", says that if p is false, then "p => q"

is true. That makes zero sense to me, because I haven't dropped the

ball - I have no reason to say that the conditional is true, because I

don't have any evidence for it.

I took a section from velleman's book to answer this:

Figure 1.16.

To help us fill in the undetermined lines in this truth table, let’s look at an example. Consider the statement “If x > 2 then x² > 4,” which we could represent with the formula P(x) → Q(x), where P(x) stands for the statement x > 2 and Q(x) stands for x² > 4. Of course, the statements P(x) and Q(x) contain x as a free variable, and each will be true for some values of x and false for others. But surely, no matter what the value of x is, we would say it is true that if x > 2 then x² > 4, so the conditional statement P(x) → Q(x) should be true. Thus, the truth table should be completed in such a way that no matter what value we plug in for x, this conditional statement comes out true.

For example, suppose x = 3. In this case x > 2 and x² = 9 > 4, so P(x) and Q(x) are both true. This corresponds to line four of the truth table in Figure 1.16, and we’ve already decided that the statement P(x) → Q(x) should come out true in this case. But now consider the case x = 1. Then x < 2 and x² = 1 < 4, so P(x) and Q(x) are both false, corresponding to line one in the truth table. We have tentatively placed a T in this line of the truth table, and now we see that this tentative choice must be right. If we put an F there, then the statement P(x) → Q(x) would come out false in the case x = 1, and we’ve already decided that it should be true for all values of x.

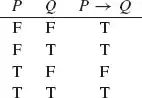

Finally, consider the case x = −5. Then x < 2, so P(x) is false, but x² = 25 > 4, so Q(x) is true. Thus, in this case we find ourselves in the second line of the truth table, and once again, if the conditional statement P(x) → Q(x) is to be true in this case, we must put a T in this line. So it appears that all the questionable lines in the truth table in Figure 1.16 must be filled in with T’s, and the completed truth table for the connective → must be as shown in Figure 1.17.

Figure 1.17.

Of course, there are many other values of x that could be plugged into our statement “If x > 2 then x² > 4”; but if you try them, you’ll find that they all lead to line one, two, or four of the truth table, as our examples x = 1, −5, and 3 did. No value of x will lead to line three, because you could never have x > 2 but x² ≤ 4. After all, that’s why we said that the statement “If x > 2 then x² > 4” was always true, no matter what x was! The point of saying that this conditional statement is always true is simply to say that you will never find a value of x such that x > 2 and x² ≤ 4 – in other words, there is no value of x for which P(x) is true but Q(x) is false. Thus, it should make sense that in the truth table for P → Q, the only line that is false is the line in which P is true and Q is false.

Can I then go around saying "I've proven that if I drop a ball, it

will hit the ground", even though I've never dropped a ball to test

it?

When you make a proof you must always assume that your premises are true, then you must say, If I would drop the ball then it should always hit the ground, if that does not happen even if it starts from a valid reasoning, it is not sound.