Although double modals are not “standard” written English outside of “dialect” writing, they are common enough, particularly in the north of Britain and in some parts of North America. Perhaps the best reference is the chapter on “The English double modals” in Linguistic Change Under Contact Conditions (ed. Jacek Fisiak; Mouton De Gruyter, August 1995), where on page 209 it reads in part:

The historical home of the current “double modals” would appear to be in Scotland and Scot English (Montgomery 1989) since Scots speakers settled in great number in northern Ireland in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and later generations migrated from there to the American south. [...] The double modals [that] have begun to emerge from the dialect literature in the last decade or so have begun to receive some attention by investigators working in the programmatic frameworks that they apparently threaten.

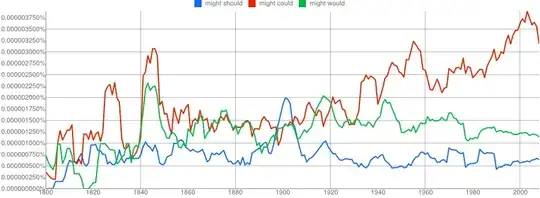

There is a great deal more of interest to the topic immediately following that. It’s interesting that they remark above that the usage has begun to emerge “from the dialect literature”, presumably into the main stream of standard writing. This Google n-gram shows that “might could” in particular is growing:

Note that I have not accounted for any noun uses of might in the n-gram above, such as “political might could” or “military might should”. Googling The Economist or the New York Times for double modals turns up plenty of false positives of that particular sort, so the previous n-gram alone should not be taken as actual proof of anything. It is perfectly possible that (say for example) “military might” is simply becoming a more common topic of discussion, so further work would be needed to winnow out any actual evidence from such results.

Another source attesting to the use of double modals in Modern Scots is A.J. Aitken in The Oxford Companion to the English Language (Oxford University Press 1992. p.896).

Finally, this source argues that this is not an “illiterate” use:

The use of the double modal is definitely not "illiterate," but rather typical of regional dialect. It just happens to be largely, if not exclusively, confined to spoken language or reported speech, which says more about the intolerance of dialectal forms in "standard" written English than it does about the education level of the speaker. It's generally true that more educated Southerners tend to avoid this construction, but that's due to a prejudice of perception, not to any inherent inferiority of the use.

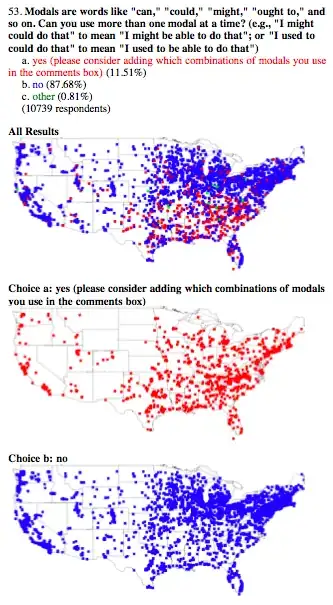

In fact, I doubt whether the most common double modals, "might need to" and "might've used to," would clang in most English speakers' ears. However, this dialectal use is indeed mostly concentrated in the South and South Midland, according to the Dictionary of American Regional English, which also gives the following complete list of actually occurring forms, which I think is surprisingly varied:

may could, may can, may will, may shall, may should, may supposed to, might could, might oughta, might can, might should, might would, might better, might had better, may used to, might supposed to, might've used to, may need to, and might woulda had oughta (the last four are listed with no intervening punctuation; I don't know if it's a typo or not).

The use of most double modals is fading in the more northern reaches of its original range, which used to extend as far as the Pennsylvania German community. Most commonly, the may/might element takes the place of the adverb probably; in other cases, it's the can/could element that is substituted for be able to. Actually, many of the forms cited in DARE are not double modals, but examples of the way that might is being directly substituted for "probably," such as "might better" (you probably [had] better) and "might supposed to" (you are probably supposed to).

Double modals are quite common in Northern English (that's England English) and Scots. The settlement patterns of people of Scottish ancestry in the southern U.S. might would account for the concentration of the usage there.

In summary, I don’t think one can answer the question of whether might could is a “correct” construction. All we can say is that some speakers consider it grammatical, and others do not.

Personally, I myself would avoid it in formal prose or formal speech, because I do not perceive it to be part of the higher registers of spoken or written English. Nevertheless, it is perfectly common (and therefore grammatical) for many speakers on both sides of the Atlantic, and I would not hesitate to use a double modal in casual and colloquial registers. I rather like the construct, to be honest; it has a certain parsimony of phrasing that I appreciate, and it imparts a certain folksy tone to one’s words that may (or may not) come in handy.

It also seems to be on the increase. I’m not one to speculate why this might be, but the initial reference work I gave [Fisiak 1995] would seem to be the place to go to delve more deeply into that sort of question, perhaps with supporting evidence from DARE.